The dry and unforgiving desert posed a deadly threat to everyone, all except for the Nabataeans of the ancient city of Petra. These Nabataeans made use of their knowledge as desert nomads to not only survive, but conquer the cruel landscape and create the utopian trade kingdom of Petra that overflowed with wealth (Bedal 2002). Wealth, which was not only reflected in commerce, but through extravagant exhibits of clean water.

The inhabitants of Petra possessed such an excess of water that they regularly indulged in luxuries such as swimming pools, man-made waterfalls, and fountains (Bedal 2002). Among all these luxuries, the most precious display were the gardens, specifically the Petra Garden and Pool Complex. This garden of Petra demonstrates the Nabataeans’ affluence and mastery over water throughout the early Roman to late Byzantine era.

This image is provided by Graham Racher.

The plants that the Nabataeans chose to grow in the Petra Garden and Pool Complex reflects the commercial concerns of the city, and therefore aids in understanding the prosperity of the people throughout time. For example, during the 1st century BCE to 1st century CE of the early Roman era, the primary plants that were grown in the gardens include grapes, olives, figs, and cereals (figure 1). As the city transitioned into the late Roman era of the 2nd to 3rd century CE, the Nabataeans started to grow a greater amount of Thymelaea passerina (Spurge flax) plants (figure 1). From here to the end of the Byzantine era, the Petra Garden continued to cycle through growing primarily grapes, olives, and spurge flax.

Of the plant remains that were studied from the garden and pool complex, it is important to note that the vegetation not only consisted on relatively drought-tolerant crops such as olives and flax, but also of highly water-demanding species such as palms, Panicoideae grasses, and violets (figure 1). The presence of these plants indicates that the Nabataeans of Petra possessed the sufficient technological prowess to harness the required amount of water to grow them, primarily through underground water conduit systems such as seen in figure 2. Furthermore, the presence of grapes and olives, as well as other plants typical to that of Roman culture reflects the influence of said Romans on the Nabataean people. This suggests that the aesthetical and some of the commercial differences between the two cultures were comfortably amended following the Roman’s conquest of the city.

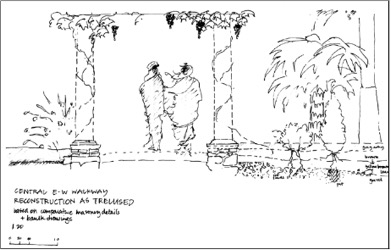

This image is provided by by Kathryn L. Gleason. (Bedal et al. 2011)

The water-related features within the Petra Garden and Pool Complex allows us to better envision the sheer wealth of water wielded by the Nabataeans. For example, the gardens not only possessed underground waterways used to sustain the variety of vegetation being grown, but also installed purely ornamental structures such as a pond to complement the terraces (Bedal 2011). Walkways made of fine masonry marked a leisurely path throughout the garden, lined with various sizes of trenches and pits that once grew the impressive collection of plant species (Bedal 2011).

A hypothetical reconstructive depiction of the ornamental walkway can be seen in figure 3, which includes some of the plant species that would have been cultivated in the garden. As such, although the Petra Garden did house various agricultural plants throughout the early Roman to late Byzantine era, the recreational aesthetic of its architecture signifies that the Nabataeans were not heavily reliant on these crops. Instead, the people of Petra were able to afford to pour all their excess water into creating a lush garden that which primary function was to be for pleasure.

It should also be noted that the ornamental nature of the garden remained consistent throughout the eras; the aesthetic-based architecture remained mostly untouched (i.e. fine masonry of the walkways), and although some of the underground water pipes were repurposed for other future projects, the garden continued to flourish (Bedal 2011). The prosperous nature of the garden can also be seen through the plant remains identified in figure 1, which shows consistently large amounts of vegetation from the early Roman to late Byzantine era (Group 1 through group 4). As such, the continued upkeep and development of the Petra Garden and Pool Complex is indicative of the resilience of wealth among the Nabataeans even after surviving under two different governing cultures.

L. Conyers, E. Ernenwein, and L. Bedal 2002. “Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) Mapping as a Method for Planning Excavation Strategies, Petra, Jordan. E-Tiquity Number 1,” January.

Leigh-Ann Bedal, “Desert Oasis: Water Consumption and Display in the Nabataean Capital,” Near Eastern Archaeology 65 (2002), pp. 225-234.

Leigh-Ann Bedal, Kathryn Gleason, and James Schryver. 2011. “THE PETRA GARDEN AND POOL COMPLEX, 2007 and 2009.” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 55 (January): 313–28.

Ramsay, J.H., and L.-A. Bedal. 2015. “Garden Variety Seeds? Botanical Remains from the Petra Garden and Pool Complex.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 24/5: 621–634.