You can do it.

Only you can do it.

You can’t do it alone.

You won’t be alone if you take care of your people.

A Personal Tribute to Patrick Henry Winston

YIDA XIN

RECEIVED ON 30 JULY 2019

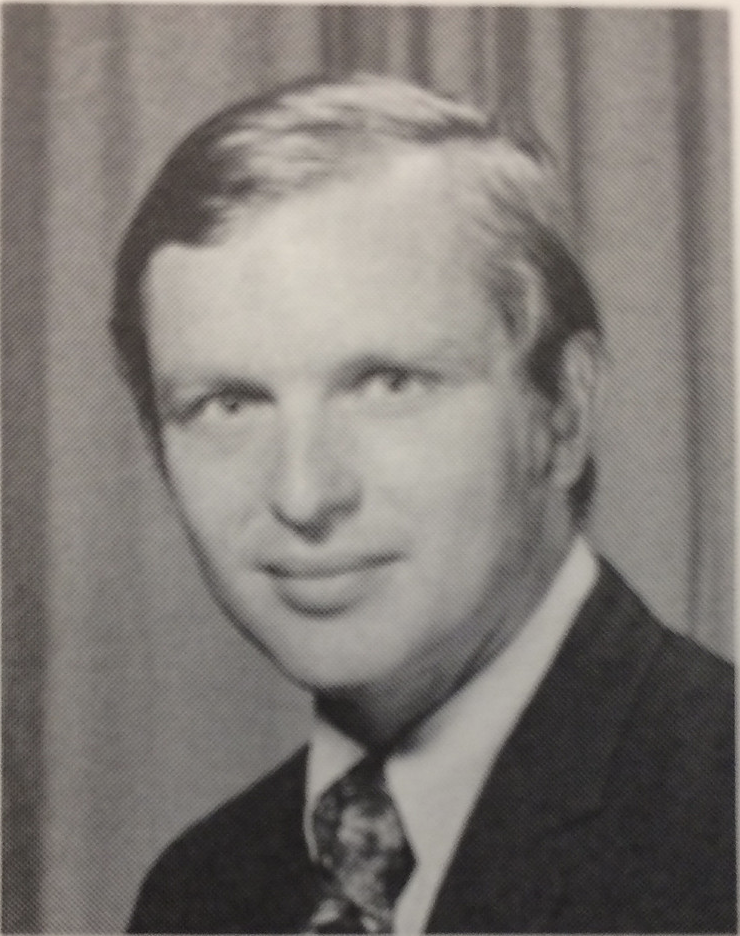

Patrick Henry Winston was, by all standards, a rock star in the field of Artificial Intelligence.

In 1970, Patrick wrote his Ph.D. thesis, in which he explored—under the improvisational supervision of his advisor, Marvin Minsky—the theoretical difficulties of learning, and wrote in Lisp a blocks-world program that could perceive blocks and block-enabled architectures (e.g. arches), build semantic-net descriptions about what it sees, compare those descriptions, and use such comparisons to learn definite knowledge in the blocks world. That computer program was able to learn to generalize its existing knowledge when comparing a baseline example architecture with a new example, and specialize its existing knowledge when comparing a baseline example with a near miss. That was the first effort ever in making machines learn things in ways that resemble how humans learn things. Some say that was “real” Machine Learning, much unlike statistical Machine Learning and neural-net Machine Learning, whereby programmers would program their computers to slavishly crunch through hundreds of billions of data points, which is nothing like how people learn new things, but has become popular because the theory behind them are much more understood and much easier to implement, and because this kind of big-data crunching is practically allowed for due to the tremendous computing power that we have today.

Then, in the 1970s and 1980s, Patrick continued his thesis work and focused extensively on studying—and re-producing in computers—cognitive processes that could enable human-like learning and reasoning via drawing analogies between remembered experiences and encountered new situations. Inspired by Minsky’s theory of learning from negative knowledge, Patrick, along with his colleague Ryszard S. Michalski, pioneered Variable Precision Logic, which is a type of formal logic that allows rule-based systems to flexibly draw conclusions about and take actions in the real world based on how much and what kind of information is fed to these systems. In today’s AI terminology, Variable Precision Logic resembles—in spirit, not in theoretical details—Vladimir Vapnik’s idea of Learning Using Priviledged Information.

After that, in the 1990s and onward, having been inspired by Roger Schank’s Conceptual Dependency Theory since the 1970s and having been a life-long believer in the central role that stories play in human intelligence, Patrick, alongside his fellow travelers, built the story-understanding system now known as the Genesis Story Understanding System. Genesis reads stories that are carefully prepared in simple English, reasons about connections between story elements, concludes high-level concepts such as revenge and Pyrrhic victory, and reflects on those conclusions to recursively tell stories about its storytelling. With the goal of accurately modeling and thoroughly understanding human intelligence, Patrick programmed into Genesis his lifetime’s worth of research work and insight, and, before his untimely death, continued to improve all aspects of Genesis together with his fellow travelers.

Patrick, who died on 19 July 2019, was born in East Peoria, Illinois on 5 February 1943. A true MIT lifer, he arrived in 1961 as a prospective undergraduate, and never left, having received the B.S. in Electrical Engineering in 1965; the M.S. in Electrical Engineering in 1967; and the Ph.D. in Computer Science in 1970, under the supervision of Marvin Minsky. The day Patrick passed his Ph.D. dissertation defense, Marvin shook his hand and said, “Congratulations, Professor.” Very shortly after that, in roughly 1972, Marvin handed over to Patrick the position of Director of Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, and after a mere 25 years, in 1997, would Patrick finally step down from that position. Some folks who had and have been around MIT for a while still sometimes gather and say to one another, “Remember back when Patrick Winston was director of AI lab?”

For those of us who are ever so fortunate to have had close interactions with Patrick, every one of us have our own story of how Patrick changed our lives by way of inspiring us in one way or another, and how we then flocked to Patrick’s lab to join him for the sense of mission of cracking the mystery of human intelligence and, at the same, the lots and lots and lots of joy while carrying out that mission. I, like others, have my own story about that, and let me tell my story…

…It was the second semester of my junior year in college, I was a pre-medicine student double-majoring in Economics and Neuroscience. I was frightened by the thought and the cost of going to medical school, so I told my father, who made me study pre-med in the first place, that I didn’t want to continue on with the whole med-school application stuff, even though I was just finishing my last two courses of all of the pre-med requirements. My father said (actually in Mandarin Chinese), “Ok, that’s fine. What will you do then?” And I told him I didn’t know, either. I, too, never gave much thought on what to do if not medicine; but, I knew deep down that becoming a doctor was not what my life was meant to be. I needed, and still need, excitements and meanings in my life, and I couldn’t see how becoming some kind of doctor owould help me accomplish that. I told my father that, as he knew, I had been interested in how the brain works and I was studying brain science, so perhaps I could get a Math minor along with my Neuroscience major, and maybe go to some graduate school studying this thing called “Neural Computing” or “Mathematical/Computational Neuroscience” or whatever it’s called. “Above all,” I said, “if I do a Ph.D., you wouldn’t need to pay for that.”

After a bit of going back-and-forth, my parents eventually told me to knock myself off, which I did. At that point, I hadn’t done any math after I took Multivariate Calculus in 12th grade and Linear Algebra in freshmen year. But I consulted with my Neuroscience department advisor, who told me that I had gotta start reading research papers, so I started banging my head against those research papers. That turned out to be fruitless, because research papers are generally unintelligible, especially to a young and stupid undergrad who was in his first few days of deciding to go down this rabbit hole called research. So then, I decided to abandon research papers and turned to textbooks on Neural Computing and Mathematical/Computational Neuroscience, thinking that textbooks were meant to educate and so they should be more intelligible. That also turned out to be fruitless, because there weren’t a whole lot of those textbooks around, and the ones I could find were roughly 2% neuroscience stuff and 98% mathematical modeling stuff. At the time, I simply didn’t know enough math to read those books. I was very discouraged, and I decided it was time to reflect a little bit on just exactly what I had done with my life.

Upon reflection, I immediately realized that I was not interested in the biology of the brain. What I had—and have—been interested in, since childhood, was how we think; but every time I described my interest to others, I always phrased it as “I’m interested in how the brain works.” I thought that, because the ability to think was given rise to by the biology of the brain, I had to study and understand the biology first before I could move on to studying and understanding how we think. In retrospect, what I didn’t know was the huge gap between an understanding of neurobiology and an understanding of how we think, which is a gap that nobody to this day knows exactly how to bridge. In retrospect, what I refused to think about was targeting directly at studying and understanding how we think.

But life had to carry on. Because I had no luck with papers or textbooks, I thought of another type of resources: video lectures. Because I discovered my lack of interest in neurobiology and my lack of knowledge in mathematics, I decided to look into video lectures that teach just math, instead of Neural Computing or blah blah blah. That should be easy, I knew there were lots of math stuff online. I consulted with the Math department chair, Prof. Morris Kalka, on which math classes I should take if I wanted to study Neural Computing, and he recommended Differential Equations, Probability, Scientific Computing, and Statistical Inference. I was overwhelmed, but I said OK and thought to myself that I’d start studying the prerequisites. So I wandered on the web, browsing all kinds of lectures that might have to do with those math topics, and I wandered into the MIT 6.034 Probabilistic Inferences lectures on OpenCourseWare.

I noticed the course name was Artificial Intelligence, but I didn’t know what the hell that was. I didn’t even immediately make connections between Artificial Intelligence and those Hollywood killer robots. I just thought, “What a teacher!” because I felt like I understood all of probability theory at the end of those two lectures. I took note of the teacher’s name: Patrick Winston. I put his name down on my list of professors that I was going to email one-by-one, because I learned that I needed to reach out to people and talk with them about their research and pretend that I was interested, so I could stand a fighting chance for graduate school. I decided to email everyone on that list over the weekend.

The weekend rolled around. It was April 9, 2016, a Saturday. I can’t remember who I already emailed, but I sent out my email to Patrick Winston, saying something like “Hi Professor Winston, I apologize for reaching out to you out of blue like this. I’m interested in studying Neural Computing in graduate school, but I couldn’t understand the papers I read and I don’t know what math classes I should take. …… Thank you very much for your time…” I sent the email at 4:51PM, and 14 minutes later at 5:05PM, as I was still writing my next email, I got a reply. “Yida,” he wrote, “Never Apologize.” That immediately struke me and, to this day, continues to influence the way I talk with any person on Earth, because just as I was then panicking and timidly begging around for some general advice about what to even study, there was this MIT professor who straight-up told me to dignify myself no matter who’s at the other end of whatever correspondance.

Professor Winston went on to say that “Most scientific papers are unintelligible because the authors either don’t know what they are doing or hallucinate that they are writing clearly.” That helped me re-collect my confidence: It wasn’t entirely because I was under-informed and stupid, but also because those authors couldn’t get their ideas across. To this day, I grasp this point to my heart and soul, especially as I continue to read Patrick’s various writings ranging from the 1970s to the 2010s, appreciating how uniquely brilliant of a writer he was.

Still in the same email, Professor Winston went on to recommend Signal Processing and Machine Learning to me, because Signal Processing is the math we need to model the world, and Machine Learning is a generally useful bag of tools. I decided to look into those mathematics, and also look into this guy’s own research and perhaps read some of his papers. But I wanted to finish his OCW video lectures first. I started with the first lecture, in which he talked about his research program in developing a computational theory of how people think.

That hit the bullseye. Tears came into my eyes.

Since childhood, I had been interested in how we think. Whenever I talked to the adults, however, they would either not take me seriously, or tell me that was an ultimate question that no brilliant scientist in the world had the gut to go head-on against. Well, guess what, now there was this MIT professor who had been devoting his life to studying how we think.

I decided to send Professor Winston another email, but this time, I expressed some thoughts I had been contemplating in relation to human thinking—just like how I expressed my curiosities to adults around me when I was a child. Professor Winston got back to me again, criticizing some of those thoughts and offering alternatives. From that point on, I gradually came to know that Patrick Winston was one of the most renowned and important professors at the world’s arguably most elite research institute, whom I could actually rely on getting back to my email most of the times. So there would be quite a few email exchanges between me and Patrick, and that was how he introduced me to Marvin Minsky, to the field of Artificial Intelligence, and to the Genesis system.

Eventually, I ended up dropping out of all of pre-med, Economics, and Neuroscience, and finished up just enough math courses to graduate from Tulane with a B.S. in Mathematics. It was a difficult year, and my constant feeling throughout the year was that there was too much to get done, that there simply wasn’t enough time, and that I started too late doing the work I was meant to do. But then, somehow, I was fortunate enough to be admitted by BU—really, any school at all—as a Ph.D. student in Computer Science. I have to admit, a very important part of the excitement was that I could finally come to Boston, which meant I could travel across the Charles River to the MIT campus and knock on Patrick’s door. And I did that.

In October of 2017, I emailed Patrick about the possibility of attending his 6.833 course during Spring of 2018, he said, “I generally have room for one such person. You are that person for spring 18.” The course, however, had to eventually be canceled, because Patrick was going to be out-of-action for all of March, and he decided that the 6.833 experience would be compromised without his presence for an entire month. It later turned out he managed to stay in-action as much as possible and was absent for only two weeks total, and he did offer a different version of 6.833, which I missed out.

In early May of 2018, I emailed Patrick once again. This time, I finally asked him if we could meet up and talk about research. I admitted to him that I perhaps should’ve done this much earlier. After briefly mentioning that he had had some personal trouble, he eventually offered to meet on May 31, and that was when we met up, in person, for the first time.

We scheduled for 9 o'clock in the morning; I arrived at Stata Center at 8:30. I decided to take a few minutes to walk around, having never been to Stata Center before, and eventually got lost. As 9 o'clock was approaching, I started to panick: The last thing I wanted was arriving late at my first meeting with Patrick Henry Winston! So I literally started asking everyone I bumped into in the hallway where the office 32-251 was, and finally a lady asked me back, “Who are you trying to find?” I said Professor Patrick Winston, she said “Oh, Patrick!” and started instructing me how to walk over to 32-251. I followed the instruction and finally arrived at 32-251, where I saw all the colored “How to Speak” flyers taped onto the drawer set by the door, as well as the name tag “Patrick Winston” hanging on the wall by the door frame. I sheepishly stuck my head over into the door frame and peeked into the office, and I saw a pair of eyes behind a pair of glasses, behind two computer monitors. It was Patrick Winston!

Before I reached my hand over to knock on the door, the pair of eyes suddenly turned up and started looking right at me. My heart skipped a beat. He then lifted his head above his monitors so that I could see the smile under his eyes, and he said, “You must be Yida.” He said that sentence in such a PHW way. I nervously replied “Yes,” and he started to look down at his desk while standing up from his chair, with a mysterious smile hanging on his face. If you ask me now, I think at the time I interpreted that smile as “Good lord it’s been a long time and you’re finally here!” Then, as he was still standing up, he looked up—in such a PHW way—at me again, pointed to his espresso machine by the door, and said, “Coffee?” I nervously said, “No thank you, I…ummm…I’m good.” He looked down again, “Okay. I need to have some.” And he started making coffee for himself.

We talked about a lot of general things during that first meeting. We talked about the future of AI; we talked about the state of the art for cognitive science, as well as prominent researchers in the field such as Josh Tenenbaum; we talked about neural computing, whereby he brought up Stephen Grossberg as a persistent pioneer and the work of Staelin on mathematical models of neural-spike computation; we talked about Deep Learning and criticized the inability of feedforward nets to reflect on their own action. And, we talked about something I was contemplating for about two weeks before I met up with him: that I wondered about how to experiment with Minsky’s K-line idea using artificial neurons. I said to Patrick that maybe it was possible to build bundles of 100 neurons, designate those bundles to be the lowest-level mental agents in Minsky’s theory, have each bundle learn some conceptual primitive, and program these bundles into an architecture that can flexibly adjust its own organization based on the problem it’s put to solve. Patrick said, “See, that’s the kind of thing you can’t do if you don’t already know how to do it.” But that wasn’t it: he recommended that I should read a paper written by one of his students, which had implemented some aspects of the K-line idea using Deep Q-Learning, and he sent me the paper. I then, in all of my seriousness, discussed the energy issue with him that we ought to make sure to build Artificial Intelligence in energy-efficient ways so that AI could help us solve the global warming problem, not further cause the problem, as Josh Tenenbaum suggested in his 6.S099 lecture during Spring of 2018. Patrick said, “See, that’s the kind of thing you can’t do if you don’t already know how to do it.”

Over the past year, I had the unique opportunity to be mentored by Patrick, and that has further broadened my view toward research, toward life in general, and toward humanity. One time, we were taking the elevator down together, and he conveyed to me, in a very much father-to-son tone, “You can’t have too much on your plate, otherwise you won’t have any time thinking up good ideas. Well, marriage helps, or can help, so I got married. My wife’s just as busy as me though.” He paused for no more than 1 second, and then resumed, “Well anyhow, maybe you ought to get married or something.”

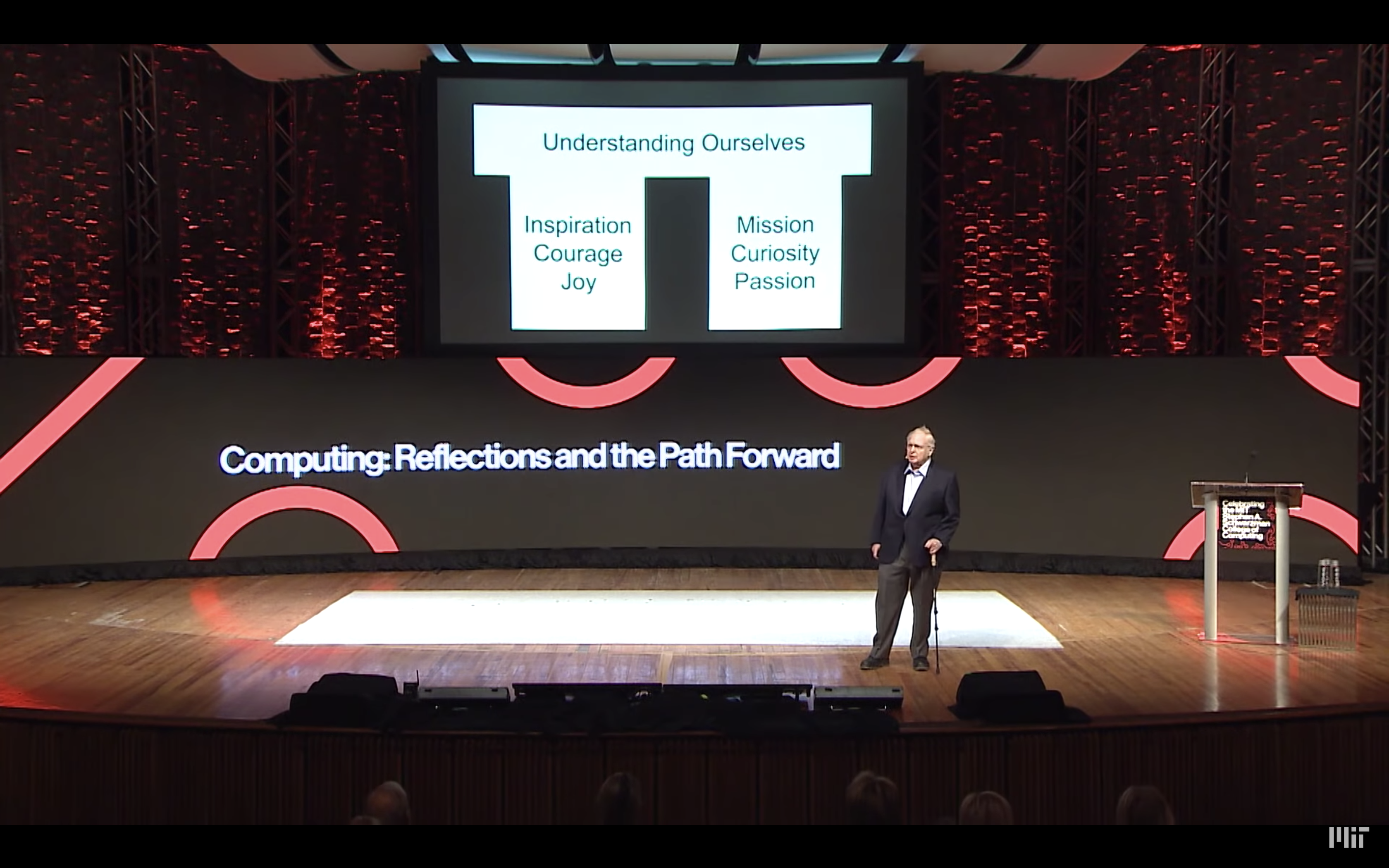

Another time, we were walking side-by-side over to attend Eric Horvitz’s talk at 32-123, and at that time, Patrick was walking with his walking stick. He said, “You’re still interested in neural nets.” I said, “Yeah, more or less.” He then immediately said, “You’re interested in neural nets, because you think it’s the right way, or because you like it?” I paused. He detected my pause, “Or both, I guess?” and then he turned to look me in the eyes. I slightly nodded, and he gave back a firm nod. I was a little nervous at the moment, because I knew that Patrick was never too hot on not just Deep Learning, but also any straight-up mechanistic approach whatsoever. But I decided to screw up a little courage, and said to him, “Well, I like neural nets as mechanisms. I think when we take a top-down approach and eventually we keep getting down and down, we’re gonna get to a level where we need to think about mechanisms. So I think we should understand the mechanisms better before that happens.” I looked at him, and he gave another firm nod while watching his way. And as we arrived at 32-123, which is a staircased lecture room whose door is all the way up in the back of the room, Patrick wanted to get a front-row seat, so he had to walk all the way down to the front of the room. He asked me, “Will you join me?” I said, “Of course.” He said, “Okay, then help me down.” So I held his left arm, as he used his right arm to operate his walking stick, and we walked down, staircase-by-staircase, from the back of room all the way to the front. When we finally got down there, Eric Horvitz, being a Technical Fellow at Microsoft as he was and is, came over and greeted Patrick. Patrick greeted back, turned to me and said “Save me a seat, will you,” and walked over to have a chat with Eric Horvitz; some others were also there. I saved Patrick the seat on my left.

And that’s where the story has taken us: Patrick’s death was untimely and a tremendous loss—a loss that’s perhaps indescribable in words. But, it’s far from the end of story. Ever since Patrick pulled me from the rock under which I lived, I have continued to be fortunate to get to know the works of many, many good people who have always been just as devoted to demystifying human intelligence as Patrick had always been. The future of cognitive AI research—whether the next 20 years or the next 50 years—looks more propitious than ever. As this community move forward altogether, I will never forget that Patrick was the man who always knew the right way, and the warrior who never was afraid to speak to anyone whatsoever about the right way.

Of course, his legacy will be remembered, his senses of mission and joy will be inherited, and his unfinished mission of cracking the mystery of human intelligence will be continued by us the right way. When the day comes that Artificial Intelligence finally gets to a human level and finally serves good to humanity, as Patrick had always wished and reminded us of, I will take up a front-row seat while that is all happening, and I will save Patrick the seat on my left.